Austerity impacts on headcount

So what has happened to trade union membership in the period during which the UK economy has limped its way out of recession and run straight into the path of austerity?

Earlier this year, the National Statistics figures in Trade union membership 2012 were rosier than expected, showing that the number of employees who were members of unions or staff associations had jumped over the last year by 60,000 — a 1% rise. Membership had kept pace with the rise in the number of UK employees between the end of 2011 and 2012, with union “density” — the proportion of employees who are members — remaining stable at 26%.

However, looking across the whole four-year period since the low point of recession, there has been a decline in union membership. Between the last quarter of 2009 and the last quarter of 2012, the number of employees who were union members fell by about 250,000 — a contraction of 3.8%. This was a faster fall than the drop in employee numbers.

Union membership in the public and private sectors declined at different points in that four-year period, but overall the worst fall was in the public sector. Between 2009 and 2012, 217,000 union members “disappeared” in the public sector (-5.3%), while losses in the private sector were limited to 38,000 (-1.5%).

In terms of industrial sectors affected, the biggest chunk of union membership decline was in public administration, where union membership shrank by 86,000, or 9%.

Manufacturing was the second worst, losing 60,000 — an 11% decline. And the industry suffering the third most serious loss of members was finance, where membership sank by 56,000 — a massive 25% contraction.

The government figures cover membership of all unions, including non-TUC unions such as the Royal College of Nursing, and also of staff associations. The most recent membership figures for unions affiliated to the TUC show how the trends have impacted on those particular unions.

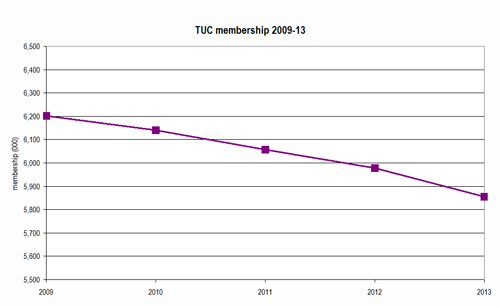

TUC

Overall, the total tally of membership of all 54 TUC-affiliated unions was 5,855,368 at the beginning of this year. This is 346,905 fewer than at the start of 2009 — suggesting that these unions’ combined membership has fallen by 5.6% in those four years.

It should be noted that this overall decline does not directly translate as “lost” members. On the one hand a number of large affiliates, including public services union UNISON, construction union UCATT and the Community union, have undergone “cleansing” of their membership records since 2009, exaggerating the apparent loss.

On the other hand, however, the latest TUC total is boosted by the inclusion of a small number of new affiliates over the period, meaning overall loss from affiliates is slightly understated.

But while the combined picture for the period after the crash is on a downward curve, the trends for individual TUC affiliates do not follow a consistent shrinking theme. Looking at the largest unions, whose fortunes have the biggest impact on the movement overall, membership patterns have varied widely.

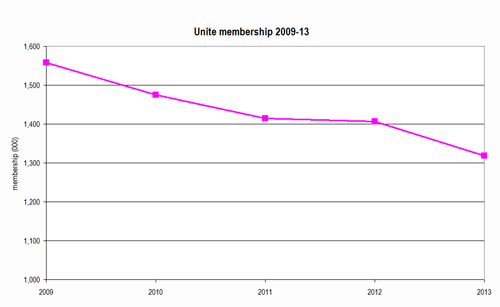

Unite

The most obvious difficulties have been faced by the largest UK union, the Unite general union. In 2009, two years after its creation with the merger of the TGWU and Amicus, its quoted membership was almost 1.6 million. This has now shrunk by 15% to a little over 1.3 million. The union has faced hits from several directions, including continued mass job losses in finance, manufacturing and construction.

PCS

Another large union that has faced significant contraction in the period is the PCS, whose members largely work in the civil service and its agencies. PCS membership expanded by 16% in the decade before the 2008 crash, and rose again in 2009-10. However, as soon as the coalition government came to power, with its desire to hack away at the public sector, numbers began to recede to the 263,000 recorded in 2013.

CWU

The post-crash years have also seen a big squeeze on the CWU postal and telecommunications union, despite its strenuous efforts to organise the private telecoms companies. Its numbers fell by 13% between 2009 and 2013, bringing membership down to little over 200,000. In this case, the decline was a long-term trend — the CWU had already contracted by 18% in the 10 years before the crash.

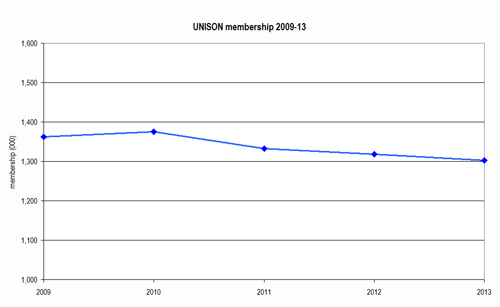

UNISON

The second British “super-union” — public services union UNISON — saw a more modest fall in membership over the years coming out of recession, of 4% .

The union’s predominantly local government and health service membership have in the later part of that period faced large-scaled redundancies. However, the union has so far managed to stem the losses to some extent through recruitment blitzes and national campaigns, such as the multi-union pensions strike of November 2011. Membership fell by just 1.2% in the last year.

And more positively, half of the largest 10 TUC affiliates have actually seen a rise in membership over the four years since the nadir of the recession.

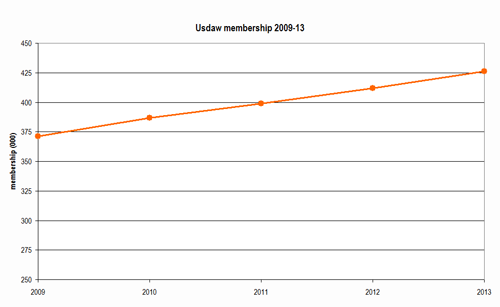

USDAW

The most impressive example is retail and wholesale union Usdaw, which has grown by 15% in the last four years — a net addition of 55,000 members.

The union’s steady rise is in addition to a 20% expansion over the decade leading up to the crash. The union has capitalised on the growing employment in this sector, but still tends to concentrate its recruitment efforts in the companies where it has existing strong organisation.

Education unions

The other key area of growth for TUC unions since 2009 has been in (largely secondary) education. The three largest teaching unions have all expanded over the last four years — the NUT by 11%, the NASUWT by 7% and the ATL by 5%. (The Educational Institute of Scotland, however, has contracted by 9% in that period.) This period of growth continued a decade of expansion before the crash.

However, it is possible that this long upward curve for the teaching unions may be levelling out. The two largest – the NUT and NASUWT — did continue their growth in 2012-13, but this was at a substantially slower pace than in recent years. NUT membership rose by 2,563 — or 0.8% — compared with an average rise of 3.5% over the previous three years. And NASUWT membership crept up by a net 317 members — a rise of only 0.1% — compared with an average 2009-12 growth of 2.3%.

Meanwhile, the ATL, whose membership largely lies in schools and further education colleges, shrank by just over 4,000 members (3.2%) last year, after three years of average growth of 2.7%.

The union said it had noticed “an increase in the number of teachers retiring early”, which could have an impact on membership levels. However, a more significant factor behind the apparent slowdown in growth in 2012-13 is that ATL, like most unions involved in the 2011 pensions strike, experienced a peak in membership at that time. These would show up in the 2012 figures, making comparisons with the following year less than typical.

Indeed, the memberships for all three main teaching main unions are still higher than they were at the beginning of 2011, before the dispute.

Smaller unions

Outside the largest unions, there are also some positive signs from the smaller specialist health unions. Membership of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, for example, rose by 9% between 2009 and 2013, while that of the Society of Radiographers (SoR) rocketed by 21%. Membership also rose in the Hospital Consultants and Specialists’ Association, the British and Irish Orthoptic Society, the British Dietetic Association and the Society of Chiropodists & Podiatrists.

Warren Town of the SoR says the growth in his union, like a number of professional unions, is about the service the union provides. “The numbers of radiographers has not increased that much … the success is down to identifying what it is that members want, improvements in communication, constant engagement with members and being honest about what we can and cannot do”.

It seems that the unions have taken a hit from the 2008 crash and ensuing recession but, in terms of membership, has managed to offset some of its worst potential effects.

Even the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills noted that the contraction in union membership has been slighter than in previous recessions. Its annual bulletin — Trade Union Membership — points out: “Coming out of the recession in 2008-09, [union and staff association] membership … declined by 7% between 2008 and 2011, compared with an 18% decline in trade union membership following the previous recessions between 1990 and 1993.”

This is quite good news, but there is clearly no room for complacency. As the new Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, noted last month, the UK is undergoing “the weakest recovery on record”.

On top of that the government is showing no signs of letting up on its public sector austerity programme. It will be another few years before we can truly see how the unions have stood up.

![[cover image]](images/issue/LR201309.jpg)