Double-dip recession hits settlements in last pay round

The UK is seemingly out of the double-dip recession. The National Institute of Social and Economic Research, the respected think tank, has estimated that the economy grew by 0.8% in the third quarter of 2012, ending three quarters of falling output.

However, after a prolonged squeeze on earnings and continuing uncertainties in the European and global economies, a weak recovery of the kind seen in 2010 and early 2011 is more likely than strong growth in 2013.

Employers, surrounded by a sea of conflicting information about the economic outlook, may be cautious about costs. In this environment, union negotiators who have adapted for recession and austerity may find they need to deploy the same approach once again in 2012-13 pay round.

Just like the wider economy, pay bargaining seems to have been back in recession. The general level of wage settlements has been lower, with pay freezes affecting not just the public sector but parts of the private sector too. And the workforce was, once again, split between the “haves” with a pay rise of some kind and the “have-nots”.

Median pay increase

In the 2011-12 pay round, half of all deals increased their lowest basic rate by 2.5%. That marks a small fall in the midpoint or “median” level of pay rises, down from 2.75% in previous pay round

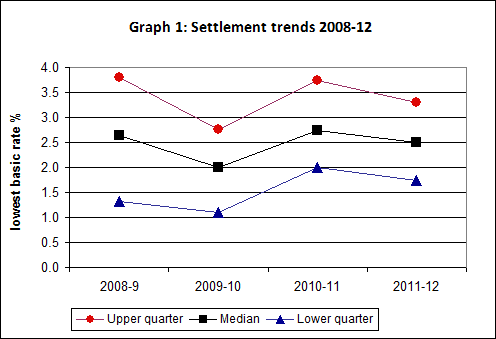

It’s a pattern that has been seen before. Looking back over the last four years, pay settlement levels fell, rose in 2010-11, but since then have fallen again. In other words there has been a “double-dip pay recession”.

The downshift was repeated at the top and tail of settlements: the top quarter of pay deals were worth 3.3% or more against the previous figure of 3.75%, and the bottom quarter were worth 1.75% or less against the previous figure of 2.0%.

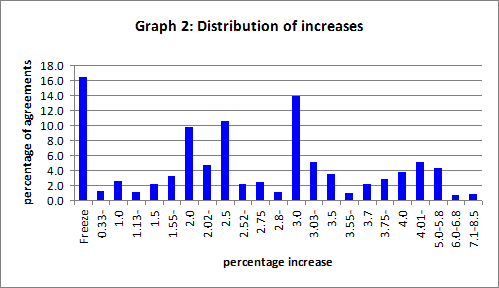

Even though 2.5% was the middle of the range, that doesn’t mean it was the most common settlement level. Around a tenth of pay deals raised their lowest basic rate by that amount but more that were either frozen or had a bigger 3% increase (see Table 2 over).

The headline results take no account of the numbers of workers who are covered by the different agreement. When the figures are weighted to reflect approximate numbers covered, the median emerges as just 1.0% — down from 1.83% in 2010-11.

Over the last four pay rounds the trend has been more down than up, dropping from 2.4% in 2008-09 and 1.75% in 2009-10, before briefly rising in 2010-11.

There’s been a similar downward trend among the weighted top quarter of settlements, down from 2.6% to 1.8% in 2011-12.

And at the other end of the spectrum, since 2009-10, the bottom quarter of workers has consistently been covered by agreements that awarded no increase at all on their lowest basic rate.

Union reps taking part in an LRD survey at the end of last year were sceptical about how far inflation would fall in the first half of 2012 (see Workplace Report, January 2012, pages 15-17). They seem to have been right.

Inflation

Last autumn inflation, under the Retail Prices Index (RPI), inflation was over 5%. At the start of this year it fell to 3.9% but that wouldn’t have been apparent until mid-February, by which time many pay deals would already have been completed.

Inflation was much slower to fall to around 3% — that didn’t happen until May and June — by which time over 85% of deals in the pay round would have already come into effect.

Over one in 11 of agreements in the survey (9%) had some sort of explicit link to inflation. If the fall in inflation came too late to exercise much downward pressure on pay bargaining, it certainly had an impact on inflation-linked settlements. They increased lowest basic rates by a median of 4.1%, far higher than the overall 2.5% mid-point in this year’s survey. Those coming into force in January were higher still, worth around 5.3%.

Inflation-linked increases were almost entirely the result of existing long-term deals in the private sector.

Long-term pay deals

Altogether 27.1% of pay rises in 2011-12 were the result of either an existing or a newly-negotiated long-term agreement. That’s less than in 2010-11 (31.8%) but would probably have been higher if it hadn’t been for the government’s imposed two-year pay freeze policy.

Excluding the imposed public sector freezes, long-term deals of all kinds have as usual produced higher pay settlements in 2011-12. These average out as a 3.5% rise compared with annual or short-term staged deals with a 2.5% rise.

Inflation-linked deals had the advantage, but existing deals without an inflation link, and newly-negotiated long term deals, still had an edge, delivering median pay rises of 3.0%.

Some long-term deals were “front-loaded”, delivering their main benefit in year one with smaller increases coming later on— examples include Allied Bakeries (Glasgow), Celtic Energy, Rio Tinto Alcan (Lynemouth) and GlaxoSmithKline (Ware).

They can also be “end-loaded”, delivering a rise just before the next pay deal, as happened with the Tesco Distribution (Blue Book) agreement.

Among the most valuable long-term deals in the survey, the Offshore Divers agreement provided a 7.1% increase based on RPI plus 1.5%. The agreement at Quorn Foods provided increases equivalent to RPI plus 0.5%, with an upper limit of 7% and a lower limit of 0%, over three years.

London Underground was the only public sector deal in the survey this year with an inflation link. Its long-term deal delivered an increase of 4.2% from 1 April 2012, based on February 2012 RPI of 3.7% plus 0.5%.

Even without an explicit inflation link negotiators may have built in other safeguards. The 2010 BT NewGRID three-year agreement provided a 3% rise in January 2012 but had a re-opener clause allowing for further talks if the November 2011 RPI was above 3.2% (in fact it was 5.2%). The CWU communication workers’ union was able to secure an additional £250 lump sum for members, but couldn’t get the company to give ground on a consolidated award.

Long-term pay deals 2011-12

| Increase on lowest basic pay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of deal | Percentage of 2011-12 deals | Lower quartile | Median | Upper quartile |

| New long-term deals | 7.9% | 2.1% | 3.0% | 4.0% |

| Existing long-term deals, no inflation link | 11.2% | 2.2% | 3.0% | 3.5% |

| Existing long-term deals, with an inflation link | 8.0% | 3.7% | 4.1% | 5.2% |

| Annual and short-term staged deals | 72.9% | 1.0% | 2.5% | 3.0% |

Note: Excludes imposed settlements arising from the goverment’s pay freeze policy

Public sector pay policy

Chancellor George Osborne’s public sector pay policy has clearly been a significant cause in the double-dip pay recession. In his 2010 emergency budget, Osborne called for a two-year pay freeze, but with staff earning the full-time equivalent of £21,000 or less to be paid “at least” £250 a year.

The freeze was due to be applied from 2011-12, but for civil servants not already covered by a legally binding deal pay was frozen in 2010-11, on the promise that they would “exit the freeze” ahead of other groups.

Existing long-term deals — for groups like the police and school teachers in England and Wales — were also allowed to run their course, so roll-out of the freeze was effectively staggered over successive pay rounds. As a result, some affected groups— like the Forestry Commission— were only in the first year of their pay freeze during the 2011-12 pay round.

So there were differences in when it was implemented, but also in who implemented it and how. These will carry over to the new two-year 1% limit announced in last year’s autumn statement and now starting to be implemented.

The civil service, NHS, and school teachers and police officers were all affected. Local government employers adopted the freeze but not the £250 minimum (except at individual councils like Wigan and Buckinghamshire). The unions (GMB, UNISON and Unite) calculate that members’ pay packets have been cut by 13% in real terms that is, after allowing for inflation.

Other local authority-linked groups with frozen pay included the youth and community workers, educational psychologists, craft workers and sixth form college staff, although the fire service secured a 1% pay rise in July.

In other parts of the public sector, away from the influence of UK central government, there were a variety of pay rises, including the BBC (2% or £400), British Waterways (3%), and the publicly-owned banks —RBS (a below-inflation imposed rise) and Lloyds (a 2.5% pay pot).

Royal Mail and Post Office agreements were unconstrained by the freeze and delivered rises worth between 3.03% and 3.97%.

Higher Education saw £150 consolidated increases on all pay points, while an imposed settlement on English further education colleges raised the minimum pay point by 2.2% (while paying £200 to staff below £21,000 and £125 a year above that).

These arrangements alone should have resulted in some growth in overall public sector earnings. But there were also differences in the way the pay freeze was implemented. Around a quarter of the public sector employers adopting the £250 minimum payment applied it to their basic salaries as well as to individual employees, but many did not.

In these cases, lowest basic rates would have risen by varying amounts, from 1.29% at National School of Government and 1.38% in Further Education Wales to 1.8% in the NHS Agenda for Change agreement and 2.16% at the Higher Education Funding Council for England. In some cases — at the Ministry of Defence and the Northern Ireland Civil Service, for example—rises of this kind were even higher.

Uneven as it has been, the pay freeze policy had a dramatic effect. Lowest basic rates in the public sector rose by a median of just 1% in 2011-12 with the top quarter worth 2% and the bottom quarter worth zero. When numbers covered are taken into account, the median also fell to 0%, and that carries over to industrial sectors dominated by public sector employment.

The public administration sector covers 7% of agreements in the survey but almost a third (32%) of the workers. With one exception (G4S Altcourse, Ryehill and The Wolds Prisons, 2.5%) the sector is made up of state services and had all-agreement and weighted medians of 0%.

The education sector covers 8% of agreements and 12% of workers. It had a below-average level of pay settlements (including freezes) resulting in a median pay rise of 1.0%, 0% weighted. With a few exceptions, such as Accenture Learning (2.86%), these are mostly state service agreements.

Health covers only 1% of agreements in the survey, but 18% of workers. Apart from a handful of private/voluntary sector agreements, such as Age UK with a pay bill increase of 2.25%, health is dominated by state service agreements and pay freezes. The median was 0% but the weighted figure was 1.8% reflecting the NHS Agenda for Change agreement that raised its lowest spine points by £250.

Private sector trends

Compared with the public sector, pay trends have been a bit stronger in the private sector. Median settlements were only a little lower than in the last pay round at 2.91% with upper and lower quartiles of 3.5% and 2%. However underlying problems are more apparent in the weighted figures, where a quarter of the private sector workforce is covered by agreements in which the lowest basic pay rate was frozen.

Part of this must be due to the influence of private sector deals negotiated on a multi-employer basis, many of them in sectors such as construction or “other manufacturing” that have fared badly in the recession. They delivered an un-weighted median of 2.5% median compared with 3% for private company deals.

But on an un-weighted basis one in 10 private sector deals (10%) ended in a pay freeze. In last year’s survey only 3.7% of private sector bargaining groups had pay freezes and, under normal circumstances, any at all would be unusual.

The construction industry and local media sectors were prone to pay freezes in 2011-12 but there was no shortage of examples elsewhere including food manufacture (such as Golden Wonder), fuels (CPL Industries), carbon fibres (Bluestar Fibres), defence (QinetiQ), wholesale (Makro), retail (Matalan drivers), bus transport (Cardiff Bus), air travel (Monarch Airlines), finance (Bank of Ireland), housing (Look Ahead), security (G4S, Security Plus), professional bodies (Chartered Management Institute) and the voluntary sector (RSPCA).

In some cases, freezes came with lump sum payments attached, such as the £500 payment for Matalan drivers, or the £1,000 first stage in Babcock International Marine & Technology Division’s Devonport’s new three-year deal. Others came with the possibility of self-financing bonus payments, commitments on redundancy, increased allowances or improved holiday pay or entitlement.

Top deals

Balancing the low deals and freezes there have certainly been some higher negotiated settlements, injecting a bit of spending power back into parts of the labour market. One in six private sector deals (17%) produced pay rises of 4% or more.

Top deals included Jaguar Land Rover with 6.1%, Ford — 6%, Network Rail — 5.7%, Yorkshire Water — 5.2%, Vauxhall Motors — 5%, South West Trains — 4.75%, BMW Mini — 4.5%, Northern Rail — 4.45%, Toyota — 4.3% and Eurostar International — 4.1%.

The motor industry, high tech engineering, energy and water, and transport operators stand out in this list, but the pattern in other mainly private-sector industries was more mixed.

The energy, water, mining and nuclear sector is small, accounting for 5% of agreements and just 1% workers, but it had the highest level of pay settlements in the survey at 3.5%, 3.1% weighted. These were mainly private company agreements (such as Scottish and Southern Energy, 3.5%) but included one multi-employer agreement (Offshore Divers, 7.1%) and one in the public sector (Magnox, 1.5%).

The manufacturing (engineering and metal products) sector represented a bigger share of the survey’s agreements (9%) but still only accounted for about 1% workers covered. It too had an above-average level of pay settlements (3.0%, 4.0% weighted).

Transport and communications accounted for a large slice of agreements in the survey (30%) and accounted for about the same proportion of workers covered in the survey (4%) as manufacturing. The sector had an above average level of pay settlements (3.0%, 3.5% weighted). It combines private company agreements (for example, BT NewGRID, 3.0% plus £250) with a public service element (such as Royal Mail Letters, 3.5%).

Manufacturing (chemical, minerals and metals) includes 4% of agreements in the survey but less than 1% of the workers. It had an above-average level of pay settlements (3.0%, 3.0% weighted) and reflects private company agreements only (such as A Schulman, 3.0%).

The other manufacturing sector accounts for 12% of agreements in the survey but only 2% of workers covered. Settlements in this diverse sector were closer to the survey average (2.53%, 2.53% weighted).

They reflect a combination of private company agreements (like Hanson Building Products/Hanson Brick 2.9%), multi-employer agreements (such as Furniture JIC 2.53%) and one public sector agreement (Remploy, 1.0%).

The finance and business services sector accounts for 8% of agreements and 6% of workers covered. Where basic increases could be calculated (the sector has a lot of performance-related pay deals) the level of pay settlements matched the overall midpoint of 2.5%, 2.5% weighted).

These were mainly private company agreements (such as HSBC, 2.5% pay pot) but with biggest currently in the public sector (HBOS, and Lloyds Banking Group, 2.5% pay pot) and some quangos (such as Acas, pay frozen, £250 paid below £21,000).

In retail, wholesale, hotels and catering (5% of agreements, 10% of workers) settlements were a little below the average trend (2.5%, 2.0% weighted). These are mainly private company agreements (such as Tesco 2.0%) but include one multi-employer agreement (Retail Co-ops, managers, 2.5%) and one public sector agreement (Royal Mail Holdings – Quadrant Catering, 2.75%).

The three agricultural wages board orders in the survey represent less than 1% of settlements but about 2% of workers covered. They delivered an average level of pay settlements (England and Wales, 3.2% on lowest grade; Scotland 2.5%; and Northern Ireland 2.4%).

The diverse other services sector (12% of agreements, 1% of workers) had a below-average settlement level (2.0%, 1.6% weighted).

It ranges from private company agreements (such as G4S Cash Solutions (UK), clerical & administrative, 0.75%) to housing associations (for example, Family Mosaic Housing Group, 0%) and publishing (Trinity Mirror Midlands, 0%). There are also private multi-employer agreements (such as Regional Theatres (TMA), 2%, 3.0% for grade 5); and public sector agreements (such as Vehicle and Operator Service Agency, 0%).

Finally, construction (1% of agreements, 11% of workers) has been dominated by pay freezes affecting most of the multi-employer agreements in the sector (such as the CIJC, 0%) but also includes Building & Allied Trades (1.0%).

Full settlement details availabe for free online

The survey was drawn from LRD’s Payline database and included 823 agreements covering 7.84 million workers, within which 713 agreements covering 7.37 million workers provide our statistics on the percentage increase on lowest basic rates.

Full details of the settlements involved in the latest pay round analysis, including pay, hours and holidays, can be viewed in a pdf document that is available online at: www.lrd.org.uk/index.php?pagid=102

Allowances

Allowance payments can add significant amounts to the pay packet so how they were handled in pay negotiations in 2011-12 would have been important. Allowances were referred to in almost 11% of settlements in this year’s survey but in most cases that was simply to confirm that an agreed increase would apply to (“flow through” to) allowances, maintaining their value relative to basic pay.

Despite the difficult bargaining conditions, only in a handful of settlements did pay rises not “flow through”, or only did so in part. Set against that there were instances such as in the national construction agreements, of allowances being increased even when pay was frozen; or otherwise improved.

At Princes (Church Stretton), for example, a 2.5% increase to pay came with a 25% shift allowance uplift. The allowance for Offshore Caterers prevented from returning ashore on the same day increased from six to eight hours, while there were allowances for additional duties at Carlisle Cleaning Alstom West Coast Traincare. Lodging allowances improved at Volker Rail, while travel allowances were enhanced at EDF Energy Cottam Power Station.

Progression

Maintaining the value of progression and incremental pay systems was another potential challenge in 2011-12. These payments usually allow salaries to rise while employees gain experience in their job and can be quite independent of the annual pay rise.

Private sector deals seem to have confirmed their role. A 4% January pay settlement at Scottish Power Energy Network came with a grade progression increment of 5% for eligible employees. Technician grades at Invista Textiles (UK) had a 3.5% increase but were also in line for performance-related pay for “meeting” or “exceeding” expectations.

Monmouthshire Building Society had an across the board increase to salaries and scales of 2.5% that, along with service increments, increased the total wage bill by 4.5%. And at Ulster Television staff currently on a developmental path were to be progressed through their grade, subject to satisfactory performance, as well as receiving a pay rise of 2.5% or £600.

Paying for performance

The recession does not seem to have undermined the appetite for performance-linked payments of one kind or another although there’s a risk they might open the door to too much management discretion, like the “zero per cent” pay awards that have tended to plague the finance sector.

Pay is linked to performance in one way or another in one in six (16.8%) of the pay settlements in the survey. East Midlands Airport’s existing long-term pay deal included a commitment to develop and implement a new variable pay mechanism based on operating profit. In some cases, on the other hand, performance payments were ruled out rather than in, as was the case at the Scottish Government, Scottish Prison Service or South Staffordshire Water.

Collective bonus payments featured in just under 5% of deals, usually offering payment of anything between £200 and £1,500 on condition that financial or other targets are met. These were more likely to be in manufacturing or industry settlements (for example, Siemens Industrial Turbomachinery), although there were examples from travel (Gatwick Airport), leisure (Ladbrokes Northern Ireland) and energy (British Gas, Scottish Power).

Just over 4% of deals provided individual bonus payments separate from basic pay. They occurred mainly in the civil service, despite the pay freeze. The Royal Parks Agency set aside £51,700 to fund individual performance payments of up to £550: excellent performers could also be awarded between £150 and £750 through other reward schemes. At the Seafish quango, a 1% increase was accompanied by a performance related bonus — of up to 5% of salary — for a quarter of its staff.

On a more challenging note, in just under 5% of agreements money allocated for the 2011-12 pay rise for individual employees was entirely dependent on their performance, typically measured through some sort of appraisal. Arrangements of this kind are very common in the finance sector where this year the budgets allocated have been quite small.

The Co-operative Banking Group, for example, had a 2.5% overall pot from which to pay individual awards ranging from 0% for “unacceptable” up to 7% for “outstanding” (dependent on position in the pay range). Many other finance, insurance and business service companies followed the same approach, typically putting up between 2% and 3% of the pay bill for the purpose. At Barclays Bank, the amount was increased from 2% to 2.5% as a result of the renegotiation of the terms of the existing long-term deal.

Outside of the finance sector organisations taking this approach included Age UK (paybill up by 2.25%, performance increases from 0% to 3.5%). At Allianz Engineering Inspection, where the pay pot was 2.5%, all staff received 2% if their performance was satisfactory, then the top one-third of each team received an equal amount of 0.5% of the team’s total salary increase.

At the Atomic Weapons Establishment there was an annual performance budget of 3% with individual awards ranging from 0% to 5.6%. BT put 3% into arrangements of this kind for particular bargaining groups. And at Hyde Housing Association a paybill increase of 2.5% was used to provide individual increases (a £500 bonus was also paid).

Where arrangements of this kind apply unions will often try to limit the scale of variable payments and include some kind of across the board or non-conditional element. Partly-performance based individual settlements cropped up in around 2.5% of deals. UK Life Services (Diligenta), for example, had a 2.25% increase from 1 April 2012 with additional performance related increases of up to 0.75%.

At Prudential (UKIO), a 3% merit pot was to be distributed by managers based on individual performance and position in scale. However a “matrix” was agreed (a table setting out pay rises for particular levels of performance, often with position in the pay scale also taken into account) which meant that people who met all their objectives were likely to get an increase at around 3%. The company also increased the Minimum Income Standard from £14,400 to £15,000, an increase of 4.17%.

From other sectors, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics had a 2.7% increase with discretionary additional recognition payments (up to the value of 3.9%); Alstom Power Ltd — Steam Turbines had a 2% across the board increase with 0.5% more available for performance increases; Balfour Beatty Workplace had awards based on performance but also implemented the Living Wage; BBC Worldwide had a 1% increase with a minimum underpin of £300 and a 1% pay pot for discretionary performance-related pay; and Thomson Reuters had a 2.5% increase as a minimum with an extra 0.5% awarded according to merit.

Minimum wage

Increases in the National Minimum Wage (NMW) set the pace in some collective agreements. In October 2011, a 15p an hour rise in the adult NMW boosted it by 2.5% to £6.08. At the same time, the 18-20 year-olds development rate was raised to £4.98, the 16-17 year-olds youth rate to £3.68 and the apprentice rate to £2.60.

In some sectors these minimum rates translate directly into company pay rates. That was the case at Bakkavor Pizza where pay rates startat £6.08 an hour but then rise in stages to £7.87 on days and £9.67 on nights. Smedley Foods has a similar arrangement.

Employers have to comply with the NMW, but unions and campaigners are becoming increasingly successful in getting them to take up the voluntary “living wage” idea.

But now the Living Wage of £7.20 an hour (£8.30 in London) seems to be gaining increased recognition. Its implementation accounted for lowest basic rate rises of up to 8.5% for some National Theatre staff, when the standard pay rise was 2%. It also played a role in higher rises at the Royal Opera House.

In the finance sector, the Lloyds Banking Group agreed that its pay ranges would not be below the Living Wage. And as part of a 3.2% across the board settlement all National Australia Group staff were to be uplifted to the Living Wage, taking the minimum salary to £13,104.

Moves to introduce the Living Wage were taken by Balfour Beatty Workplace and Initial (Network Rail Control & Network Rail Eurostar) while commitments to move towards or at least discuss the living wage were also adopted by the Industrial Dwellings Society and OCS Facilities Services.

However, improving the relative position of the lowest paid is likely to involve bigger pay rises at the bottom of the structure (the lowest basic rate) than for most employees (defined, on LRD Payline as the “standard” increase).

In 2011-12, it was relatively uncommon to find that the basic increase was bigger than the standard increase, except in the public sector as a result of the government’s pay freeze policy. However, Yorkshire Building Society paid 3.8% on the lowest pay rate, but 2.8% on other rates, while at the performing rights organisation, PRS for Music, the pay deal was 2.3% plus an extra 1% for all staff currently on a salary of less than £20,000 a year.

There were also a series of settlements underpinned by a cash amount that can produce higher rises for the lowest paid. The current four-year deal at ferry company Wightlink underpinned a 5.8% RPI-based rise with a £775 cash increase, worth up to 8% for some staff.

The same principle applied elsewhere in the transport sector with underpinning rises of £520 at DB Regio Tyne & Wear, £600 at Colas Rail and Northern Rail, £675 at East Coast, £750 at Merseyrail Electrics and at Balfour Beatty Rail Plant (for those on less than £20,000), and £850 at London Overground Rail for all staff paid £17,000 or less as at March 2010.

Wider agenda

Negotiators have not neglected the wider bargaining agenda. There were, for example, improvements to sick pay, including a possible reduction in waiting days at VolkerRail, and increases to paternity, carers’ and family emergency leave at Scottish and Southern Energy.

Elsewhere, maternity pay entitlement is increasing from six to eight weeks in April 2013 under the Tesco Distribution (Blue Book) agreement; long service awards have been increased at Wilkinson Stores; and a 40-hour week has been introduced at Harsco Metals (Teesside).

Subscribers to LRD’s Payline can search on specific pay and conditions to discover other improvement won by negotiators by going to: www.lrd.org.uk/index.php?pagid=18

Earnings figures lower than pay settlements

Trends in basic pay and what people actually earn differed with earnings showing lower increases.

In 2011-12, the Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that earnings (excluding bonus payments and arrears) rose even more slowly than pay, averaging out at about 1.9% a year, rather than the 2.5% in LRD’s pay survey.

Private sector earnings grew by an average of 2% across the pay round.That figure would have been a little higher (2.1%) but for the effect of employment changes. If higher-paying jobs were lost and employment switched to lower-paying or part-time jobs, for example, that could slow down the increase in average earnings (as happened in the first half of the pay round).

Public sector earnings grew by an average of 1.9% but in that case the figure was lower (1.7%) without employment changes. That could have happened if public sector job losses hit lower-paying or part-time jobs particularly hard.

Another reason for the difference between trend in pay settlements and earnings may be that only a minority of employees (31.2%) are covered by collective agreements. Union and collectively-bargained wage levels seem to have risen faster since the 2008 recession than those of other workers (see Labour Research, September 2012, pages 13-15).

On 2011 figures from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, collective bargaining covers 67.8% of employees in the public sector, but only 16.9% of employees in the private sector (although coverage is likely to be higher in larger workplaces).

Finally, the AWE figures are compiled on a different basis. They are a mean average not a median average as in LRD’s pay survey.

The mean is calculated by totalling up all figures and dividing by the number of figures to produce an average figure.

The LRD’s figure is a median which is the midpoint for settlements after they have been arranged in order from top to bottom.

![[cover image]](images/issue/WR201210.jpg)

![[PDF]](images/pdf.gif)