Tight labour market puts new vim into pay deals

The headline finding from this year’s LRD Pay Survey, covering the August 2017 – July 2018 pay round, show settlements have jumped to a 2.75% median from 2.0% on the basic increase and to 2.5% from 2.0% on the standard increase.

Behind these midpoint, or “median”, figures between a third and almost half of deals crossed the 3% threshold. The private sector led the way with median increases of 2.75% (standard) to 3.0% (basic).

Table 1: Percentage increases in settlements

| Lower 25% | Median | Upper 25% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All agreements | |||

| Lowest basic rate increase | 2.00% | 2.75% | 3.70% |

| Standard increase | 2.00% | 2.50% | 3.30% |

| Weighted standard increase | 2.00% | 2.30% | 3.00% |

| Private sector agreements | |||

| Lowest basic rate increase | 2.42% | 3.00% | 3.70% |

| Standard increase | 2.30% | 2.75% | 3.56% |

| Weighted standard increase | 2.50% | 3.20% | 3.70% |

| Public sector agreements | |||

| Lowest basic rate increase | 0.00% | 1.00% | 3.38% |

| Standard increase | 1.00% | 1.00% | 2.00% |

| Weighted standard increase | 2.00% | 2.00% | 3.00% |

New vigour in pay bargaining could simply have been a reaction to peak inflation rates in the first half of the pay round, but many employers are also struggling to recruit, finding they need to pay more or offer more attractive working conditions. Meanwhile, annual upratings of the statutory National Living Wage and voluntary “real” Living Wage have helped normalise higher pay rises.

The end of the government’s public sector pay cap should have added some oomph to the upward pay trend. That’s probably true in the case of NHS Agenda for Change and the local government services NJC settlements, but a tight framework for civil service pay continued and ministers chiselled away at Pay Review Body recommendations. And although we’ve now been told austerity is over too, many publicly funded services are short of money for bigger pay rises.

The lack of real pay growth since the 2008-09 recession — the “lost decade” — has been a huge worry for trade unions and their members. It has also been a puzzle to economists like those at the Bank of England, alongside the equally puzzling lack of productivity growth.

The Bank admits to repeatedly overestimating the prospects of pay recovery, with a sequence of “negative forecast errors” (averaging around one percentage point per year). Nevertheless, the Bank’s chief economist Andy Haldane sees compelling evidence of a “new dawn” breaking, even if it is only seen through light cloud.

Earnings growth has broken through the psychologically important 3% barrier while pay settlement figures compiled by the Bank are running close behind at 2.8% — and in some sectors, such as construction, well in excess of 3%. But do these stronger pay figures, which are confirmed in this year’s LRD Pay Survey, represent a step change towards higher living standards or is there still much further to go?

Labour market and economic pressures on settlements

Inflation has been one driver for higher pay rises in 2017-18, but another is a tighter labour market making it difficult for employers to recruit staff. Whereas inflation is now falling, labour market problems look like getting worse, so that could be important for what happens to pay deals in 2018-19.

Recent Bank of England reports — Agents’ summaries of business conditions — reveal “elevated and widespread” recruitment difficulties among construction trades, drivers, specialist engineering and IT. One factor in play is the slowing flow of EU migrants into the UK labour market. The Bank says this is proving to be a constraint in sectors, such as agriculture and food, hospitality and warehousing.

In the year ending March 2018, EU net migration fell to its lowest level since 2012 although it continued to add to the UK population (with around 90,000 more EU citizens coming to the UK than leaving).

Staff shortages are not confined to the private sector. The overall number of teachers has not kept pace with increasing pupil numbers and the ratio of qualified teachers to pupils has increased from 17.8 in 2013 to 18.7 in 2017.

In the health service, the NHS Pay Review Body has warned about an unsustainably high level of vacancies, work pressures and potential risks to care.

The recent Migration Advisory Committee report concluded that migration has not been a major determinate of the wages of UK-born workers, so on its own falling EU migration might not affect pay settlement levels, but other forces are at work.

There were 289,000 more people in employment June to August compared with a year earlier, including 230,000 in the 16-64 age range, so there is a strong demand for labour. There were 79,000 fewer unemployed and the unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest since the 1970s (4%).

Most acutely of all, there are 832,000 vacancies, a record number which is up by 35,000 compared with last year. It’s not all positive, 73,000 jobs were lost in wholesaling, retailing and motor vehicle repairs consistent with the British Retail Consortium’s prediction of “fewer but better” jobs as the industry undergoes structural change.

Table 2: Labour market trends

| Latest figure | Increase on year earlier | |

|---|---|---|

| Employed UK (June to August) | 32,394,000 | 289,000 |

| Employed 16-64 (June to August) | 31,153,000 | 230,000 |

| Employed 65 and over (June to August) | 1,241,000 | 60,000 |

| Employment rate 16-64 (June to August) | 75.5% | 0.4 |

| Unemployed UK (June to August) | 1,363,000 | -79,000 |

| Unemployment rate (June to August) | 4.0% | -0 |

| Economic inactivity UK 16-64 (June to August) | 8,748,000 | -65,000 |

| Economic inactivity rate (June to August) | 21.20% | -0.2 |

| Public sector employment UK (June) | 5,340,000.00 | -122,000 |

| Average weekly hours all workers (June to August) | 32.1 per week | -0.1 (32.2) |

| Average weekly hours full time (June to August) | 37.3 per week | -0.2 (37.5) |

| Workforce jobs (June) | 35,200,000 | 132,000 |

| Average weekly earnings (excl bonus) GB August | £492 | £15 (3.1%) |

| Labour disputes (year to August) days lost | 267,000 | 298,000 |

| Labour disputes (year to August) stoppages | 75 | 80 |

| Labour disputes (year to August) people striking | 36,000 | 47,000 |

| People made redundant or voluntary redundancy | 89,000 (3 months) | -18,000 |

| Vacancies (July to September) | 832,000 | 35,000 |

Source: Labour Market Statistics, October 2018, Office for National Statistics

Survey

This years’ survey draws on over a thousand pay settlements coming into effect during the pay round (1,062), making it LRD’s biggest pay survey to date. It includes 883 agreements with a known increase on their lowest basic rate (referred to below as the “basic increase”) and 860 with a known standard increase (what most grades or workers got). The headline results are set out in table 1.

Half of the pay deals in the survey (the midpoint or “median”) delivered a basic increase of 2.75% or more and a standard increase of 2.5% or more. It’s the first time since 2010-11 that median settlements have reached that level.

The “standard increase” measure has become increasingly important, alongside the basic increase, as Living Wage policies have accelerated growth in basic rates. Among 760 deals in the survey where both figures were known, just under 9% had a higher basic increase, while just under 2% had a higher standard increase.

These results are “unweighted”, they take no account of the number of workers covered by each deal, but do give a good feel for what’s happened across a large and diverse range of pay awards.

The weighted median standard increase was 2.3%, suggesting that a bit of caution may be needed about the strength of pay improvements in 2017-18.

The weighted figures are strongly influenced by what happened among a small group of the very biggest bargaining groups (in local government, the NHS, schools and universities, construction, the police and armed forces, the Royal Mail, civil service, retail and banking). Just 20 agreements (each covering over 50,000 workers) set the pay framework for most of the six million affected.

Bargaining groups covering 500 or more workers generally saw bigger median pay rises: basic 3.0% and standard 2.65% (compared with 2.5% for the smaller bargaining units (basic and standard). Size is not necessarily the cause of that difference.

So while some caution is needed, we shouldn’t lose sight of the improvement represented in this year’s pay figures. Among a set of 70 agreements covering at least 500 workers each, for which historic data is available, eight out of 10 had a bigger pay rise in 2017-18 than their average between 2008-09 and 2016-17.

But there have been some very varied experiences in 2017-18. The bottom quarter of pay rises were worth 2.0% or less (basic and standard) while the top quarter were worth 3.75% or more (standard 3.3%).

Inflation

Inflation under the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) reached its peak in the first six months of the pay round. CPI Inflation is now slowing, and forecast to drop towards the government’s 2% target.

However, between August 2017 and January 2018, inflation peaked at 3% based on the CPI; at 2.8% on CPI with a housing element (CPIH, the preferred measure of the Office for National Statistics); and at around 4% based on the favoured union negotiators’ yardstick the Retail Prices Index (RPI).

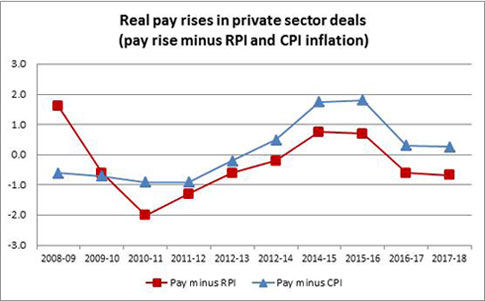

The arguments over which of these inflation measures is best rumbles on, but it matters. The chart on page 17 shows what happened to private sector median pay rises after the recession, if inflation is subtracted. If CPI is the yardstick, at least half of 2017-18 private sector deals delivered a small real-terms pay rise and so an improvement in living standards, but at least half of private sector deals were worth less than RPI inflation.

In the LRD Pay Survey, a minority of long-term deals included an explicit link to inflation — in most cases to the RPI, with fewr linked to the CPI. Altogether, the median basic pay increase among inflation-linked deals was more than 3.6%.

Table 3: Medians for staged and unstaged settlements

| Type of deal | Number of settlements | Percentage of all settlements | Basic (%) | Standard (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing long-term deals, no inflation link | 120 | 11.3% | 2.5% | 2.5% |

| Existing long-term deals, inflation linked | 93 | 8.8% | 3.85% | 3.85% |

| New long-term deals, no inflation | 100 | 9.4% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| New long-term deals, inflation-linked | 5 | 0.5% | 3.8% | 3.6% |

| Short-term staged deals | 47 | 4.2% | 3.0% | 2.5% |

| Unstaged deals | 697 | 65.5% | 2.5% | 2.4% |

JaguarLandRover surpassed that 3.6% median with a second-stage increase in November 2017 of 4.4%, based on the September RPI of 3.9% plus 0.5%. Other deals didn’t have an add-on. The Hinkley Point C Project agreement with EDF Energy provided an RPI-based 3.3% increase from 1 January 2018, while British Airways Pilots received a 4.1% increase based on the RPI for December 2017.

British Gypsum, on the other hand, is an example of a CPI-based agreement. Its first stage (2.5% across all elements of pay including production and safety bonus from January 2018) will be followed in April 2019 by an increase equivalent to CPI plus 0.2% (averaged over the three months January to March 2019). That increase will be underpinned by a minimum 2.6% and capped at a maximum of 3% and will again be applied across all elements of pay.

Nearly a third of deals in the survey are long-term deals, running for around two years or longer – a fact which, in itself, is often associated with higher pay rises. In 2017-18 the proportion of long-term deals was no higher than normal: about 30% (34% of deals with a known basic increase).

Apart from those with an inflation link, existing long-term deals delivered the same median basic increase of around 2.5% as regular one-year deals in 2017-18. However, among 100 new long-term deals, the median basic increase was higher at 3.0%.

Just over 4% of deals in the survey were short-staged deals (implementing two or more pay rises over the course of around 12 months or less). The median basic increase was 3.0%, but the standard was 2.5%, suggesting some have been used to accommodate rising minimum wage levels (other motives for short-staged agreements could be to delay the full cost of a deal, provide a top up, or change of settlement dates).

GKN Aerospace (Portsmouth) had a first stage increase of 1.35% in July. Distributor Alliance Healthcare had a second stage increase of 5p an hour in May 2018 giving the lowest paid grade an increase of 3.6% over the course of the year. Phoenix Healthcare Distribution implemented the National Living Wage (NLW) increase in April which, together with an earlier staged rise, made a total of 4.8%. In this case steps were taken to maintain a differential for other grades.

So far, the tighter labour market has seen bigger pay increases targeted at indiviuals, but that could be another factor behind higher settlements in 2017-18.

The January Thermal Insulation Contractors Association (TICA) agreement may have reflected some of these pressures by applying a 3% increase to engineering rates alongside a 2.5% increase for heating and ventilating rates and apprentice’’ (the workforce is evenly divided between those two skill groups).

On a negative note, pay freezes have not disappeared. In the LRD Pay Survey they were concentrated mainly among English FE colleges, but have also been reported in Offshore Diving, at GE (Alstom Power Limited Steam Turbines), Kiveton Park Steel and aerospace group Nordam Europe, as well as at telecoms and internet provider Level 3 Communications and the London-based Ritzy Cinema.

Industrial sector

The industrial sector settlement levels in table 4 on page 18 provide a clue as to where the strongest pay pressures are, although public sector pay policy, the “bite” of the National Living Wage and other trends also need to be taken into account.

Table 4: Median pay settlements by industry

| Sector | Basic (%) | Standard (%) | Weighted standard (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retail, wholesale, hotels & catering | 3.37% | 4.00% | 4.40% |

| Agriculture | 3.50% | 3.50% | 4.40% |

| Transport and communication | 3.31% | 3.13% | 4.10% |

| Energy, water, mining, nuclear | 3.00% | 3.00% | 3.00% |

| Manufacturing (engineering & metal products) | 2.90% | 2.90% | 3.70% |

| Manufacturing (other) | 2.80% | 2.70% | 2.50% |

| Construction | 2.50% | 2.50% | 3.20% |

| Health | 3.00% | 2.50% | 3.00% |

| Other services | 3.00% | 2.50% | 3.00% |

| Manufacturing (chemicals, minerals and metals) | 2.50% | 2.50% | 2.90% |

| Finance and business services | 3.00% | 2.30% | 3.10% |

| Public administration | 1.20% | 1.00% | 2.00% |

| Education | 0.50% | 1.00% | 2.00% |

Retail/wholesale, agriculture transport and communication, and energy, water, mining and nuclear top the list in which highest standard median increases come first (reflecting what most grades or workers got in each deal). Higher basic increases may reflect the impact of measures aimed at the lowest paid.

Public and private sector

Despite the relaxation of the government public sector pay cap, it was the private sector that led the way in 2017-18, with the strongest results since 2010-11. The median basic increase in the private sector was 3.0%, while the standard median increase was 2.75%. The weighted standard median increase was even higher at 3.2%.

In the public sector, the trend was still stuck at 1% (basic and standard median). A number of big deals involved a 2% increase for most of the workers covered, resulting in a weighted standard median increase at that level, but they were outnumbered by lower level increases.

In LRD Pay Surveys, the public sector includes Higher Education and also Further Education where there were a lot of pay freezes at college level, despite a national agreement for English colleges that involved an imposed pay award of 1% or £250 from August 2017. Further education in Wales had a 1% increase, while in Scotland the national deal is still in negotiation.

The Higher Education sector had a 1.7% increase to pay spine points 17 and above from August 2017, but there were incrementally higher increases up to 2.43% on spine points 16 up to 2.

Although the pay cap was abolished in September 2017, civil service guidance for 2018-19 (published in June) continued to insist on the need for “pay discipline”, allowing for average pay awards within the new range of 1% to 1.5%. This was “not a cap”, it was an average, and negotiators could go higher in exchange for plans to improve workforce productivity, while any increases due to the National Living Wage would be paid in addition.

In contrast, the Scottish Government announced its public sector pay policy for 2018-19 much earlier, and allowed some bargaining groups to bring their 2018 settlement date forward to April. Alongside pay progression, the voluntary Living Wage and job guarantees, it allowed for a minimum increase of 3% for workers earning £36,500 or less; a 2% pay bill for those earning above £36,500 and below £80,000; and a maximum pay increase of £1,600 for those earning £80,000 or more.

The different pattern of pay settlements in Scotland is reflected in the fact that its 2017-18 pay rise for teachers was a two-stage deal adding up to 2% from January 2018. And the implementation of the NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) agreement led to higher pay, and a different award for Doctors and Dentists (3% for all salaried doctors and dentists earning up to £80,000, and £1,600 for those earning more). It is also reflected in the unions’ dispute over the 2017-18 local government pay award and the teachers’ 2018-19 campaign for 10%.

In Wales, public sector pay arrangements are evolving (it has its own implementation of Agenda for Change) but common arrangements with England still apply in local government and school pay.

The situation for public sector pay in Northern Ireland is complicated by the lack of a functioning Executive (devolved government).

The School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB, which covers 264,000 teachers in England and Wales) had already made its recommendations for 2017-18 when the Treasury wrote to the pay review bodies (PRBs) in September 2017 calling for “pay discipline”, while recognising the need for flexibility in some parts of the public sector, particularly in areas of skill shortages.

The 2017 award was a 2% increase to the minima and maxima of the main pay range, with 1% to the minima and maxima of all other pay ranges and to all allowances.

However, since then the government has repeatedly trimmed back on PRB recommendations, undermining their independence and its claims that the era of pay caps and austerity is over.

The Prison Service Pay Review Body (25,000 staff plus 1,200 in Northern Ireland) recommendation for pay rises of 2.75% was cut to a 2% consolidated award plus a 0.75% nonconsolidated payments (April 2018).

The Police Remuneration Review Body (133,000 staff) recommendation for a consolidated 2% increase with flexibility for additional payments in hard to fill roles was cut to a 1% consolidated increase and an additional one-off non-consolidated payment (September 2017).

The Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration (217,000 staff) recommendation (4% for GMPs, 3.5% for speciality doctors, and 2% for all other doctors and dentists, from April) was altered and delayed until October (1.5% for consultants, 2% for doctors and dentists in training, and 3% for specialty doctors).

The Armed Forces’ Pay Review Body (158,000) recommendation for a 2.9% increase in base pay was cut to 2.0% from April 2018 plus non-consolidated bonus of 0.9%.

The recommendations of the Review Body on Senior Salaries (4,370) and the National Crime Agency Remuneration Review Body (4,400) were also pruned.

However, the 1,310,000 staff covered by the NHS Pay Review Body were protected by the fact that NHS Employers and NHS trades unions in England directly negotiated a three-year pay agreement (so the review body had no recommendations to make). It provided for a 6.5% cumulative increase for those at the top of AfC pay bands 2 to 8c and variable increases for other staff (worth between 9% and 29% through pay progression). There are also changes to starting salaries and restructuring pay bands (removing overlaps). It set a new minimum basic pay rate of £17,460 and is introducing other changes to progression, attendance, unsocial hours and other terms and conditions, and adjustments to unsocial hours payments.

The Local Government Services NJC deal covering England, Wales and Northern Ireland was negotiated without the involvement of central government, but also without the benefit of funding commitments underpinning the NHS’s Agenda for Change agreement. In essence, in 2018, it provided a 2%, overall increase, but up to 9.2% on lower pay points, and there will be a new pay spine in 2019. Other local government settlements in England and Wales were also worth 2% in 2017-18 (but with a bigger increase for craft workers on specified grades).

Living Wages

In November 2017, the voluntary “real” Living Wage (LW) agreed by the Living Wage Foundation rates increased by over 3.5% to £8.75 an hour and by 4.6% to £10.20 in London. Although not statutory, over 4,400 employers are now committed to paying the LW.

Entertainment and culture is one of the sectors where the LW and the statutory National Minimum Wage (NMW) and National Living Wage (NLW) are influencing pay deals.

At a national level, the UK Theatres agreement provided a 4.7% increase for staff in grades 4 and 5 from April 2018 in line with the NMW, while grades 1, 2 and 3 received 3%.

The National Theatre’s two-stage 12-month agreement from April 2018 began with a 2.5% or 45p an hour increase, whichever is the greater; but in the second stage, from November 2018, the minimum rate will increase in line with the updated London LW.

The statutory NLW rises of 4.2% in April 2017 and 4.4% in April 2018 (taking the over-25 rate to £7.83 an hour) helped keep it on its path to reach 60% of median earnings by 2020 (currently expected to be £8.62 rather than the £9.00 originally talked about).

The NLW doesn’t have to be applied across the board, but it can be applied to all age groups on a voluntary basis. The April settlement at Joseph Walkers Shortbread increased the new starters’ rate to £7.83 an hour in line with the NLW which is now applied to all age groups; the Trainee Factory Operative rate increased to £8.00 an hour, other rates of pay increase by 1.75%.

That principle was adopted by the Scottish Agricultural Wages Board (SAWB) which applied its own minimum rate of £7.83 for all workers, regardless of age (a 4.4% increase on the previous rate)

The SAWB also increased its apprentice rate by 20.8% and a number of other employers took similar steps for this particular group of lower-paid workers.

The Construction Industry Joint Council two-year agreement began with a 3.2% increase to all pay rates, but first year apprentices received a 6.5% increase.

As previous LRD Pay Surveys have shown, employers don’t have to be paying at NLW levels in order to want or be willing to negotiate higher minimum wage levels.

At Clydesdale and Yorkshire Bank, the minimum full time-equivalent annual salary increased from £15,375 to £17,000, while most higher paid staff got a 2% increase or £400, whichever was the greater.

The Valuation Office Agency increased pay range minima by 1% for higher-paid HEO- Grade 6 grades, but spot rates for the AA National grade increased by 4.3%.

Pay increases targeted at the lowest paid can lead to the compression of differentials and 2017-18 was no exception. Wholesale group Booker (now owned by Tesco) had a 4.7% increase for branch assistants from April 2018, while supervisors got a 2% increase.

Transferring money within the pay structure to allow basic pay rates to increase has become an established part of the process by which minimum wages are being raised. The current four-stage agreement at Tesco will increase hourly rates by 10.5% over the course of two years. In the third stage, from 2 July 2018, an additional 16p was added to hourly rates (taking the starter rate to £7.78, a 2.1% increase, and the established rate to £8.18).

This, however, is a “re-investment”, with Sunday and Bank Holiday premiums reduced to time and a quarter. Transition payments were to be made to anyone negatively affected with a lump sum payment worth 18 months of the difference in pay.

Equality

The 2017-18 pay round saw the implementation of Gender Pay Gap Reporting and pay equality has risen up the list of employers’ bargaining priorities.

Skills Development Scotland promised an Equal Pay Audit and an Equality Impact Assessment as part of its 2018 pay agreement.

The second year of a four year transformation of the Met Office pay model is intended to address the gender pay gap.

The Royal Parks pay system was to be reviewed for equality proofing before the 2018 pay negotiations took place.

Even the Forestry Commission’s imposed 1% pay award was subjected to an Equality Impact Assessment.

In the private sector, pay settlements for different parts of the Fujitsu workforce promised discussions about its gender pay gap, and awarded money to address gender imbalances and other anomalies.

Engineering group Selex ES (Leonardo) awarded a 3% paybill increase from 1 April 2018, but said 2.83% would be distributed using a framework seeking to reduce salary inequality across the workforce.

As part of its 3.9% pay award, Grand Central Rail promised to develop an Equality in the Workplace policy with the assistance of the recognised trade unions.

Progression

Performance-related progression is a feature of many pay agreements but a number of settlements in the pay round moved away from that selective approach, or provided guarantees about progression (which now seems to be more widely recognised as a route to pay growth).

The SSE Joint Agreement 3% increase (plus an additional 0.6% for some) came with the promise of a joint working party to agree a fairer system for rewarding progression based on skills and competency.

At carmaker Toyota an across-the-board pay deal from April 2018 of 2.9% included the consolidation of merit awards.

Meanwhile, the BBC three-year pay agreement began in August 2017 with a 2% increase but, in addition, staff who are low in their pay range were to receive an incremental increase of 1.5% to progress their pay within the pay band.

In the finance sector where performance-related pay is prevalent, the April pay deal at UK Life Services (Diligenta) was an across-the-board 2.5% increase with no variations or performance-related elements.

Job security

With fear of job losses apparently a contributor to slow wage and earnings growth after the recession, it’s worth noting that a number of pay deals on the LRD Payline database address that problem directly.

In the BT (NewGRIDgrades) agreement, the telecoms giant confirmed that it would work with the CWU communication workers’ union to avoid compulsory redundancies; and it included new redundancy terms for all staff that provide payments of up to 104 weeks’ pensionable pay.

The March pay agreement at infrastructure group Amey (Rail) included a 3% increase to basic pay and allowances (underpinned by a minimum £650, equivalent to 4.8% for the lowest paid), but it also promised no compulsory redundancies.

Pensions

The increase in minimum contributions to auto-enrolment pensions was a cost pressure during the 2017-18 pay round. However, in companies with much better pension arrangements than the statutory minimum (but who may want to change their pension offer) this is an issue that fits in well with pay bargaining.

The Rolls-Royce Staff National Bargaining Group three-stage, three-year agreement worth 3.7% from 1 March 2018, included a new pensions deal which is expected to save the firm £145 million over the next three years. It involves an agreement to keep the final salary (defined benefit — DB) pension scheme open to current active members until at least January 2024; and the relaunch of a simplified defined contribution (DC) scheme for workers who have joined the group since 2007 making it fairer, while increasing contributions for younger members. The company has also promised further contribution increases to the DC scheme from 2021.

The new two-year agreement for BT (NewGRID grades) addressed the closure of the BTPS defined benefit pension scheme in June 2018 and a new hybrid pension was introduced for existing members which will include both DB and DC benefits.

The agreement promises transitional payments of up to 10 years for existing BTPS members, and improvements to the DC pension scheme (BT Retirement Saving Scheme, BTRSS), with 70% of members getting a 25% increase in BT contributions

The existing four-year pay deal at Tube Lines promised that, from January 2017, all current staff and new joiners would have access to the Transport for London Pension Fund. In return, the RMT union committed to examining technology-driven savings.

LRD Pay Surveys are available at www.lrd.org.uk/index.php?pagid=102

![[cover image]](images/issue/WR201810.jpg)

![[PDF]](images/pdf.gif)