Membership challenge

How well equipped is the trade union movement to deal with this brazen new Tory government that is both aggressively anti-union and hell-bent on further, deeper public sector cuts?

Part of the answer can be deduced from examining what happened to union membership in the period of the Tory-led coalition.

Labour Research has examined the recently-released 2014 official union membership statistics to see what happened to union membership and penetration in the first four years after Labour’s defeat in 2010.

In that year, the country was limping out of recession — but, for workers at least, it was heading straight into a new nightmare. Indeed, 2010 proved to be a pivotal year for the union movement: in October the coalition announced what the Financial Times called “the most drastic budget cuts in living memory”. It promised to make £81 billion of cuts over the following four years — amounting to 4.5% of gross domestic product. The cuts were to hit core government departments and, in particular, local government, and were to lead to the loss of almost half a million public sector jobs.

Prior to that point, the public sector had provided some ballast to a gradually shrinking union movement.

Membership overall had been declining for decades, partly because of a huge contraction of relatively highly unionised industries in the private sector. Between 1995 and 2010, private sector union membership plummeted by 905,000.

But this was to some extent offset by a growth in public sector union membership of 381,000 in the same period. However, 2010 marked a change in these trends as the country came out of recession, mostly benefiting the private sector, and the public sector cutbacks began.

Union membership 2010-2014

Between 2010 and 2014, there was a fall in public sector union membership of 339,000.

In the same period, private sector union membership increased by 195,000 — a complete turnaround for the sector — though not enough to neutralise the shrinkage in the public sector.

Looking at how union membership fared in different industrial sectors over the first four years of the coalition, the figures show that by far the hardest-hit sector was that categorised as “public administration and defence; compulsory social security” — covering central and local government. This industrial sector lost 63,000 union members in the four years 2010-14.

Next hardest-hit were “transportation and storage”, which lost 42,000 members, and education, which lost 41,000.

It was not all bad news, however. Offsetting these losses to the unions was a 46,000 increase in union membership in “human health and social work activities” in the period 2010-14.

Another area that saw growth is “professional, scientific and technical activities”, which put on 22,000 members.

To some extent, the change in fortunes between the public and private sectors followed the change in levels of employment. In the private sector, union membership just about kept pace with increasing employment in the public sector. Union “density” — the proportion of employees who were union members — remained roughly at 14.2%.

However, in the public sector, union membership had fallen faster than employment, with union density falling from 56.4% in 2010 to 54.3% in 2014.

Overall, the first four years of coalition government saw a contraction of the labour movement — though not a disastrous one. Union membership among UK employees fell by just over 2% and union density by 1.6%.

And the most recent of those years — 2013-14 — indicated there are some glimpses of light amid the gloom.

Trade union density among employees slipped slightly, from 25.6% to 25.0%. However, the number of trade union members remained broadly stable at around 6.4 million.

And some industrial sectors actually put on members. For example, while the construction sector saw a decline in membership over the whole of the four-year period, in the final year of that period, the sector saw a sudden upturn, with 6,000 more union members recorded. Other industries which moved in a positive direction in 2013-14 included professional, scientific and technical activities, which saw a bumper 21,000 increase in union membership; education, which also expanded by 21,000 members; and health and social work which put on 16,000 union members. Smaller rises were also seen in manufacturing (6,000) and information and communication (4,000).

These brighter points in the latest set of statistics were welcomed by TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady, who said: “It’s good to see that trade union membership is as valued as ever, with the number of new members increasing in some areas.”

Pointing out that the movement still has 6.4 million members, she said: “Unions are best placed to speak on behalf of ordinary working people, to combat growing inequality and help ordinary families through the crisis in living standards.”

Workers most likely to be in a union

While the industry someone works in is probably the most significant factor determining whether they are in a union, there are also important variations according to the type of occupation they are in.

Over the years there has been a switch in the profile of union members away from those in skilled trades and production jobs and towards those in professional or technical work.

The latest figures show that, while fewer than one in five (19.0%) workers in skilled trades are members of a union, more than double that proportion — 43.7% — of professional workers are union members. This group includes the relatively highly unionised professions of nursing and teaching. The strange thing about this is that it could be argued that, in financial terms, professional workers have less to gain from being in a union, and lower skilled workers have more to gain.

The data on union membership also contains information on the so-called “trade union wage premium”. This is the percentage difference between average hourly earnings of union members and non-members. Overall in 2014, the premium for union members over non-members was 16.7%.

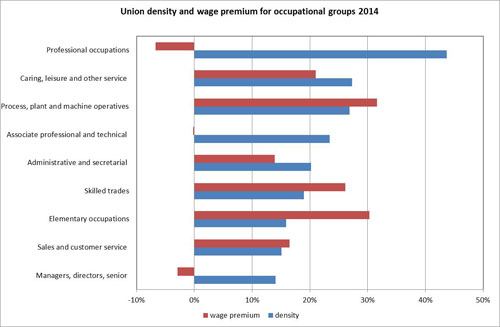

The chart below shows union density alongside the wage premium for the main occupational groups. It shows that the highly unionised professional workers have the lowest wage premium of all — in fact, union members earn, on average, 6.7% less than their non-union counterparts.

The largest wage premium, on the other hand, goes to unionised process, plant and machine operatives who, on average, earn 31.5% more than their non-union counterparts.

And union members in elementary occupations earn, on average, 30.2% more than non-members in such jobs. But these groups have much lower union densities than professionals.

The same paradox applies to the age of union members. While only 8.6% of 16- 20-year-old employees are members of trade unions — the lowest union density for any age group — they are the ones who have the largest wage premium, at 38.8%.

Crisis in collective bargaining?

What may worry unions even more than waning membership levels in recent years is the shrinkage in the spread of collective bargaining, also covered in the recent statistics.

Collective agreement coverage 2007-14

| All employees | Private sector | Public sector | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 34.7% | 20.0% | 72.0% |

| 2008 | 33.7% | 18.7% | 70.6% |

| 2009 | 32.8% | 17.8% | 68.1% |

| 2010 | 30.9% | 16.9% | 64.5% |

| 2011 | 31.2% | 17.0% | 67.8% |

| 2012 | 29.3% | 16.1% | 63.7% |

| 2013 | 29.5% | 16.6% | 63.7% |

| 2014 | 27.5% | 15.4% | 60.7% |

The proportion of employees who said their pay and conditions were covered by a collective agreement fell from 30.1% in 2010 to 27.5% in 2014.

On one level, this is just the continuation of a trend that began in 2007 — before the crash and before austerity — when 34.7% of employees were covered by collective bargaining. It has gradually declined since then (apart from an upward blip in 2011).

But the decline accelerated between 2013 and 2014, particularly in the public sector, where a much higher proportion of employees are covered by such agreements than in the private sector. The proportion of public sector employees whose pay and conditions were collectively agreed sank in that single year from 63.7% to 60.7%. In the private sector the figure fell from 16.9% to 15.4%.

Union membership in Europe

Compared with other European countries, union density in the UK, at 25% is slightly above the 23% average for all 28 EU member states.

Germany, France, Spain and Poland all have lower proportions of employees in unions than the UK and, among the bigger states, only Italy, at 35%, does better.

The highest levels of union density are in the Nordic countries: 74% of employees in Finland, 70% in Sweden and 67% in Denmark.

In part, this is because unemployment and other social benefits are normally paid out through the union.

However, it also reflects an approach that sees union membership as a natural part of employment.

The lowest levels of union membership are mostly in the 11 newer EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe, where industrial restructuring and a fundamental change in the role of unions had a major impact in the past and unions still face a difficult environment.

Nine have union density levels below the EU average, including the largest, Poland, where 12% of employees are estimated to be union members.

However, France is also one of the countries with the lowest levels of union density — just 8% — and this indicates that union membership is not the only indicator of strength.

French unions have repeatedly shown that they are able to mobilise workers in mass strikes and demonstrations to great effect, and they have a strong presence in many workplaces.

As in the UK, in most countries (Italy is an exception) union density has been falling steadily for more than a decade and a half.

However, the most recent figures suggest that membership decline has slowed in a number of countries, such as Germany, Austria and Sweden, which have seen losses in the past.

www.gov.uk/government/statistics/trade-union-statistics-2014

![[cover image]](images/issue/LR201507.jpg)